Structural Studies In Situ Show How Bacteria Infect Humans, Leading to Chronic Diseases

Understanding the biological mechanisms that support human health and drive disease is essential for developing preventive and curative therapeutics. Such an understanding requires atomic-level structural data, which can reveal interactions between therapeutic drugs and their macromolecular protein targets. Direct structural analyses of proteins in their native environment are even more important. It is well established that a protein’s native conformation is “determined by the totality of inter-atomic interactions and hence by the amino acid sequence, in a given environment.”1 This knowledge underpins the development of approaches that enable structural studies of native specimens.2 The growing need for this information has been a major driver of technological development in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), electron microscopy (EM), X-ray diffraction, and computational molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. NIH ORIP’s Shared Instrumentation (S10) Programs have provided researchers access to many such technologies, enabling structural research into the molecular basis of biological processes and human health.

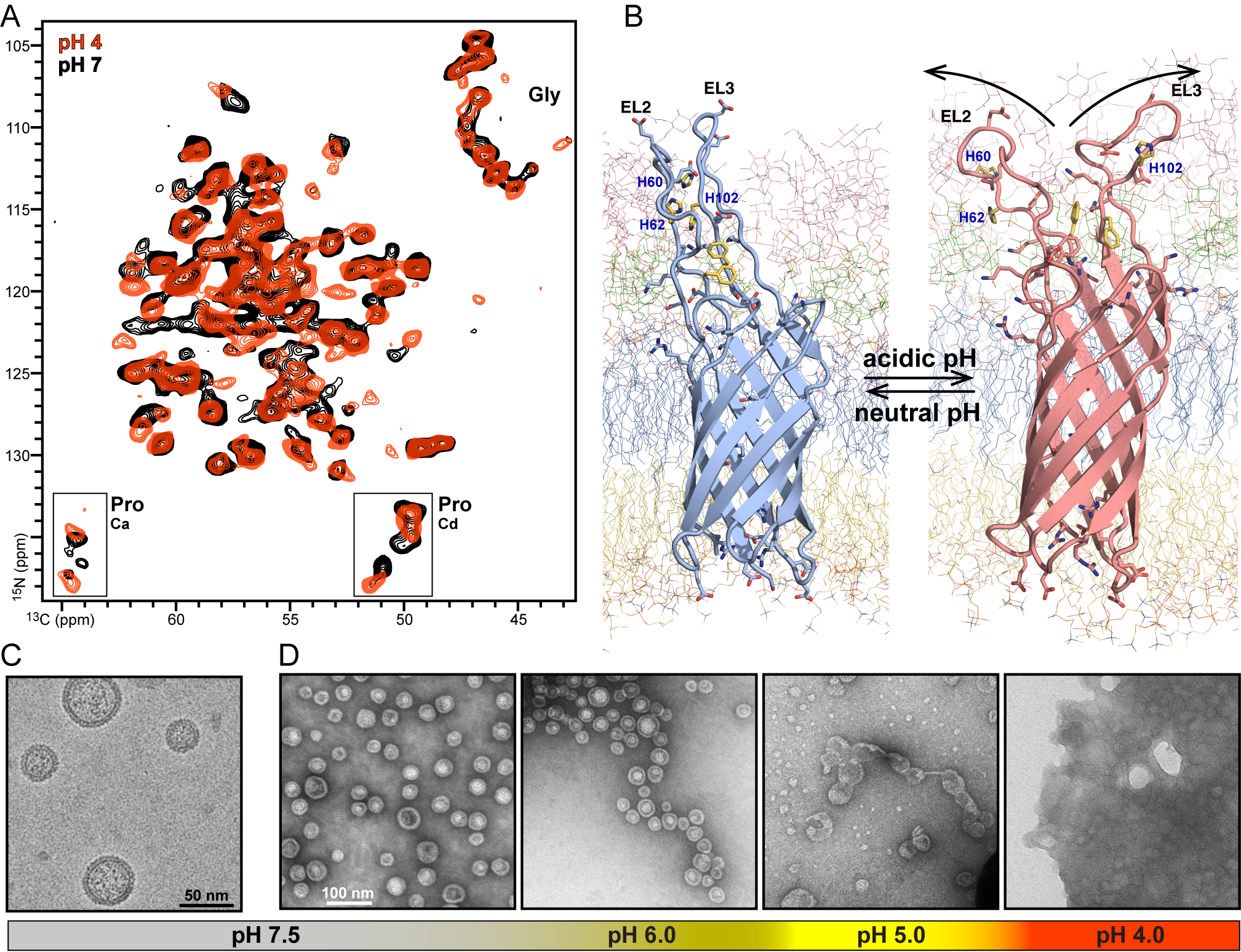

In 2020, the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) acquired a new 700 MHz NMR spectrometer through an S10 award (S10OD028716). The NMR spectrometer can analyze complex biomolecular samples, such as proteins embedded in their native cellular membranes. Much like magnetic resonance imaging, NMR relies on a strong magnetic field and radiofrequency pulses to encode, sort, and detect the atomic sites of biological molecules according to their specific chemical and structural signatures (Figure 1).

Dr. Francesca Marassi, Professor and Chair of Biophysics at MCW and the Principal Investigator on the ORIP S10 award, underscored the importance of ORIP’s support: “The resolution and sensitivity of the new NMR instrument are game-changing because they allow us to work with native biological samples without resorting to potentially disruptive additives.”

In a recent study, Dr. Marassi and her research team (Figures 2, 3) used the NMR spectrometer to analyze a bacterial surface protein associated with human infection.3 Persistent bacterial infections present significant health, economic, and societal burdens and are aggravated by the increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance. In addition, persistent infections are associated with such chronic diseases as Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, bronchitis, and cystic fibrosis. Structural studies help researchers understand how bacterial pathogens invade and colonize a human host while evading the host’s immune defenses. The knowledge gained from these studies can then advance the development of novel therapies. ORIP supports such efforts by funding high-end instruments that allow scientists to study how bacterial proteins respond to environmental cues that cause large-scale remodeling of their cell membranes.

Many cells launch tiny satellites, called extracellular vesicles (EVs). In bacteria, these satellites help ensure bacterial survival during host infection. Approximately 40 nanometers in size and 250 times smaller than red blood cells, bacterial EVs support the parent bacteria by acquiring nutrients, defusing host immune defenses, assembling biofilms that block antibiotics, and more. Despite this knowledge, however, researchers are still unclear on how EVs are formed. Using the S10-funded NMR spectrometer, the MCW team discovered that the surface protein PagC—a molecule produced by Salmonella that activates bacterial EV production—can sense acidic pH and alter its shape.3

Dr. Marassi and her team isolated EVs from PagC-producing bacterial cultures and analyzed them directly using NMR for atomic-level detection of PagC, as well as EM, for ultrastructural detection of their spherical structures (Figure 1). The team hoped to discover how acidity triggers PagC to activate EV production. “NMR allows us to probe individual atomic sites of PagC and see what happens when we change the pH,” Dr. Marassi explained. They found that three amino acids called histidines in the surface loops of PagC become positively charged in an environment with an acidic pH, which correlates with a protein structural change thought to exert pressure on the bacterial membrane that pushes it outward and causes EV formation (a process called budding). The team is continuing to probe the structure of PagC and other bacterial membrane proteins to understand how they contribute to virulence.

According to Dr. Candice Klug, James S. Hyde Professor of Biophysics at MCW, the ability to correlate structural information from NMR, EM, and EPR, another fundamental technology supported by ORIP at MCW (S10OD036246; S10OD025260), will allow scientists to understand the mechanics of EV budding, as well as other membrane remodeling events critical for pathogenesis. Dr. Fabrizio Marinelli, Associate Professor of Biophysics at MCW, is developing large-scale computer simulation technologies, powered by artificial intelligence, to gain deeper insights from the experimental data. He explained, “These combined technologies will allow us to bridge the cellular and atomic scales and understand how cells remodel their membranes to adapt to niche environments.”

The work supported by ORIP has implications beyond microbial biology and human infection. It is also important for developing new delivery systems for therapeutic drugs, which are useful for treating a broad range of human diseases, including cancers. Additional research projects supported by the ORIP NMR instruments focus on understanding the process for calcified protein-lipid deposition in chronic diseases of aging, including macular degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease.4,5 Acknowledging the critical role of ORIP’s S10 programs, the MCW team continues leveraging multiple state-of-the-art instruments to explore the molecular mechanisms that link bacterial infections with chronic human diseases.

ORIP’s S10 programs support purchases of state-of-the-art, commercially available instruments to enhance research of NIH-funded investigators. S10 awards are made to domestic public and private institutions of higher education, as well as nonprofit domestic institutions, such as hospitals, health professional schools, and research organizations. Every instrument funded by an S10 grant is to be shared with other institutions, which makes the programs cost efficient and beneficial to thousands of investigators in hundreds of institutions nationwide. For more information, please visit ORIP’s S10 Instrumentation Programs webpage.

References

1 Anfinsen CB. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 1973;181 (4096):223–230. doi:10.1126/science.181.4096.223.

2 Marassi FM, Pintacuda G. Solid-state NMR of membrane proteins in situ. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2025;94:103129. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2025.103129.

3 Wood NA, Kraft A, Shin K, et al. In situ NMR reveals a pH sensor motif in an outer membrane protein that drives bacterial vesicle production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025;122(26):e2501638122. doi:10.1073/pnas.2501638122.

4 Shin K, Kent JE, Singh C, et al. Calcium and hydroxyapatite binding site of human vitronectin provides insights to abnormal deposit formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(31):18504–18510. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007699117.

5 Gopinath T, Shin K, Tian Y, et al. Solid-state NMR MAS CryoProbe enables structural studies of human blood protein vitronectin bound to hydroxyapatite. J Struct Biol 2024, 216(1):108061. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2024.108061.

6 Dehinwal R, Gopinath T, Smith RD, et al. A pH-sensitive motif in an outer membrane protein activates bacterial membrane vesicle production. Nat Commun 2024;15(1):6958. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51364-z.