Seeing the Invisible: Detecting Early Lung Diseases with Advanced Computed Tomographic Imaging

For decades, physicians have relied on spirometry to detect chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, the global metrics derived from spirometry (a noninvasive breathing test) cannot sense regional lung damage in early disease. By the time these global indices of lung disease signal a decline, years of subtle damage to the lungs already have taken place. Dr. Eric A. Hoffman, Professor of Radiology, Medicine, and Biomedical Engineering at The University of Iowa (Figure 1), has spent his career studying human lung pathology and pathophysiology associated with inflammatory lung diseases, including COPD. He has developed imaging methods to detect that damage earlier—well before patients feel short of breath or show abnormalities on standard exams.

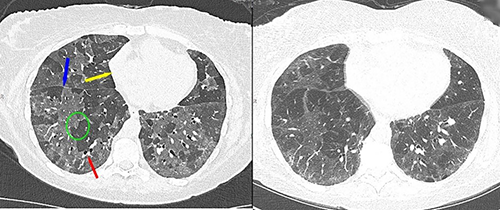

Dr. Hoffman’s research group, the Advanced Pulmonary Physiomic Imaging Laboratory (APPIL), and colleagues have pioneered computed tomographic (CT) imaging methods to study the links between lung structure and lung function.1 In the early 2000s, the group began experimenting with advanced, clinically viable CT protocols that could measure not just anatomy but also physiology—how air moves in and out of tiny peripheral air spaces, how blood flows through the intricate vascular network, and how the delivery of blood (perfusion) and fresh gas (ventilation) is optimized for normal physiologic respiratory processes. By overlaying color-coded maps of perfusion and ventilation on lung images, the APPIL group revealed striking early disease patterns—even in smokers who passed spirometry with normal scores.2 Smokers with only the faintest signs of emphysema on CT images (but demonstrating a susceptibility to emphysema) showed markedly more heterogeneous perfusion than healthy controls. The scans unveiled a new finding—patchy areas of poor blood flow and uneven air distribution that hinted at future disease. The discovery was profound: Vascular dysfunction showing as irregular, fragmented blood flow patterns—long thought to be a late consequence of smoking-related injury—is among the very first changes in the disease process.

Building on these insights, Dr. Hoffman and his colleagues were able to take advantage of advanced dual-source, dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) to measure regional lung ventilation and regional perfused blood volume (PBV; a surrogate for perfusion). This approach considerably simplified the need for dynamic scan sequences used in the earlier studies discussed above. Their DECT-PBV studies showed that after treatment with sildenafil (a vasodilator that inhibits peripheral vascular constriction occurring in response to low oxygen content), abnormal perfusion patterns in smokers with early emphysema became more uniform. This matched the patterns in smokers not shown to be susceptible to emphysema. This demonstrated that the perfusion heterogeneity was not a result of peripheral injury but may in fact be a source of lung injury. This is remarkable, because the technology allows not only visualizing the presence of early disease processes but also its potential reversibility from treatment.

In 2015, APPIL was awarded an S10 grant (S10OD018526) to acquire a new generation DECT scanner (Siemens SOMATOM Force). The new scanner used lower radiation and achieved higher spatial and contrast resolution. With this scanning technology, newer low-dose scan protocols were developed,3 and a new cohort of recruited nonsmokers has served as a comparator for assessing the presence of pathologies in numerous multicenter cohorts. These CT images—along with a growing set of image analysis tools—have served to demonstrate, for example, that small airway-to-lung-size ratio is a risk factor for COPD, even in nonsmokers,4,5 and small-vessel-to-total-vessel volume identifies a risk for rapid pulmonary function decline in young, asymptomatic smokers.6 Additional studies have shown that bone microstructure can help predict vertebral fractures in study participants with COPD;7 a novel method for assessing mucociliary clearance in genetically modified pigs with cystic fibrosis demonstrated mucous tethering;8,9 modeling studies served to evaluate potential for particulate deposition within the lungs; 10–12 and longitudinal tracking of the lung of an asymptomatic athlete with COVID-19 demonstrated disruptions in the matching of ventilation and perfusion.13 One of the group’s unique imaging methodologies used in this latter study to demonstrate the regional matching of ventilation to perfusion has been implemented in more than 700 subjects, with appropriate DECT scanners participating in the lung branch of the NIH-sponsored multicenter Multi-Ethnic Study on Atherosclerosis (i.e., MESA Lung Study).14

With the emerging capability of mapping gas transfer at the alveolar level using hyperpolarized xenon gas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the APPIL group received an S10 award (S10OD026960) in 2019 that enabled the purchase of a gas polarizer and associated imaging coils. This award attracted Dr. Sean B. Fain, Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Engineering and Vice Chair of Radiology Research at The University of Iowa and a well-known expert in the hyperpolarized MRI field, to the group. The unique capabilities of the CT and MRI modalities are integrated to expand the scope of imaging-based assessment of lung disease.15,16

The APPIL group’s CT-based imaging innovations have been central to numerous large, NIH-funded cohort studies, such as the multicenter SPIROMICS (SubPopulations and InteRmediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study), the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP), the MESA Lung Study, and others. In these studies, thousands of scans are processed using standardized pipelines established within APPIL.17 Dr. Hoffman’s laboratory leveraged their access to state-of-the-art imaging technologies to help establish these pipelines. In addition to serving as the Radiology Center for these multicenter studies—providing direction, oversight, and data analysis—the laboratory is also a clinical center, ensuring that these studies have a sub-cohort utilizing the state-of-the-art scanners. APPIL’s imaging technologies allow clinicians to watch chronic lung disease unfold years before becoming clinically obvious. The work at APPIL demonstrates that, with the right technology, even the invisible stages of disease can be seen—and perhaps one day, cured.

Despite these successes, many technical obstacles remain. “For example, beam hardening in the current CT scanners introduces scanning artifacts, which make the lungs appear less dense than they actually are,” Dr. Hoffman said. “There are still lots of unknowns to be learned about COPD pathogenesis. COPD likely has multiple origins, and we need new perspectives that potentially open new avenues for prevention and therapy.” New artificial intelligence (AI) methods, for instance, have shown that six different identifiable emphysema subtypes can be detected using CT imaging, and these have distinct associated genotypes and phenotypes.18 Studying these new phenotypes and monitoring treatment requires repeated scanning. In addition to improved images, the significantly lowered associated radiation doses are a critical new advance. By comparing information from CT and MRI scanners, the team is gaining an understanding of how to combine these two imaging methods to more easily follow the disease process from its origins while minimizing risks.

To achieve better, more robust early COPD detection and reproducible imaging across subject scans, Dr. Hoffman applied for and was awarded another S10 grant (S10OD034285) in 2024 to acquire the most advanced new generation of CT scanner, the Siemens NAEOTOM Alpha (Figure 2). This dual-source photon-counting detector (PCD) CT scanner provides constant multispectral imaging; doubles the spatial resolution, which is on the order of 0.2 mm; and improves contrast resolution, allowing for significant reductions in contrast media dosage and reductions in reconstruction artifacts, such as beam hardening (Figure 3). The new PCD-CT scanner digitally counts each X-ray photon along with their energy characteristics rather than sensing the accumulation of photons as light. By keeping track of the energy levels of the counted photons, the new scanner is capable of generating images using selected energy ranges of the photons, allowing for selective simultaneous quantification of multiple introduced or naturally occurring materials—such as iodine for perfusion, krypton for ventilation, and calcium associated with vascular plaque. The new scanner was installed at APPIL in fall 2025 and represents the only scanner of its kind in the world that is fully research dedicated.

Dr. Jessica C. Sieren, Associate Professor of Radiology at The University of Iowa and Deputy Director of APPIL (Figure 1), is excited that the new scanner is poised to allow longitudinal pulmonary CT studies for her research on integrating radiomic biomarkers with machine learning to provide insight in to cyclic changes in lung structure and function.19 Recent efforts have focused on exploring the ultra-high resolution capabilities of PCD-CT for lung evaluation,20 as well as comparing the PCD-CT with state-of-the-art quantitative protocols on energy integrating detector CT imaging systems.20,21 The current low-dose protocols3 were developed by APPIL, through use of the SOMATOM Force scanner, for the PrecISE (Precision Interventions for Severe and/or Exacerbation-Prone Asthma) Network Study, and they have been adopted as the gold standard by a number of other studies, allowing for early assessments of lung pathology and drug response. With the considerable advancements of PCD-CT imaging, it has become critical again to establish a new set of normative human data and to once again integrate standardized imaging protocols across multicenter studies. Leveraging the new opportunities offered by the PCD-CT scanner, the APPIL group is working to further characterize both lung structure (airways, vasculature, parenchyma) and function (regional ventilation/perfusion relationships along with lung mechanics).

One of the team’s key goals is early detection of COPD pathology, which would allow clinicians to determine disease etiology and tell the difference between phenotypes to better tailor patient-specific interventions and save more lives. While more work is underway, the team is grateful that ORIP’s S10 programs offer assistance to give researchers access to expensive, state-of-the-art instruments that encourage shared use and facilitate collaborations.

ORIP’s S10 programs support the purchase of commercially available instruments to enhance research by NIH-funded investigators. Each S10-funded instrument must be shared among multiple users, which ensures efficient use of instruments for research operations, enhances the cost-effectiveness of NIH’s investment, and maximizes benefits for thousands of investigators in hundreds of institutions nationwide. For more information on the S10 programs, please visit the ORIP website.

References

1 Hoffman EA. Origins of and lessons from quantitative functional X-ray computed tomography of the lung. Br J Radiol. 2022 Apr 1;95(1132):20211364. doi:10.1259/bjr.20211364.

2 Alford S, van Beek EJR, McLennan G, et al. Heterogeneity of pulmonary perfusion as a mechanistic image-based phenotype in emphysema susceptible smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010 Apr 20;107(16):7485–7490. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913880107.

3 Atha J, Eddy RL, Guo J, et al. Harmonized low-dose computed tomographic protocols for quantitative lung imaging using dose modulation and advanced reconstructions. Med Phys. 2025 Nov;52(11):e70125. doi:10.1002/mp.70125.

4 Smith BM, Kirby M, Hoffman EA, et al. Association of dysanapsis with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among older adults. JAMA. 2020 Jun 9;323(22):2268–2280. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6918.

5 Vameghestahbanati M, Hiura GT, Barr RG, et al. CT-assessed dysanapsis and airflow obstruction in early and mid adulthood. Chest. 2022 Feb;161(2):389–391. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.08.038.

6 Ritchie AI, Donaldson GC, Hoffman EA, et al. Structural predictors of lung function decline in young smokers with normal spirometry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024 May 15;209(10):1208–1218. doi:10.1164/rccm.202307-1203OC.

7 Zhang X, Comellas AP, Regan EA, et al. Quantitative CT-based methods for bone microstructural measures and their relationships with vertebral fractures in a pilot study on smokers. JBMR Plus. 2021 Mar 19;5(5):e10484. doi:10.1002/jbm4.10484.

8 Pino-Argumedo MI, Fischer AJ, Hilkin BM, et al. Elastic mucus strands impair mucociliary clearance in cystic fibrosis pigs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022 Mar 29;119(13):e2121731119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2121731119.

9 Ostedgaard LS, Price MP, Whitworth KM, et al. Lack of airway submucosal glands impairs respiratory host defenses. eLife. 2020 Oct 7;9:e59653. doi:10.7554/eLife.59653.

10 Osanlouy M, Clark AR, Kumar H, et al. Lung and fissure shape is associated with age in healthy never-smoking adults aged 20-90 years. Sci Rep. 2020 Sep 30;10(1):16135. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73117-w.

11 Ebrahimi BS, Kumar H, Tawhai MH, et al. Simulating multi-scale pulmonary vascular function by coupling computational fluid dynamics with an anatomic network model. Front Netw Physiol. 2022 Apr 25;2:867551. doi:10.3389/fnetp.2022.867551.

12 Choi S, Yoon S, Jeon J, et al. 1D network simulations for evaluating regional flow and pressure distributions in healthy and asthmatic human lungs. J Appl Physiol. 2019 Jul 1;127(1):122–133. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00016.2019.

13 Nagpal P, Motahari A, Gerard SE, et al. Case studies in physiology: temporal variations of the lung parenchyma and vasculature in asymptomatic COVID-19 pneumonia: a multispectral CT assessment. J Appl Physiol. 2021 Aug 1;131(2):454–463. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00147.2021.

14 Hermann EA, Motahari A, Hoffman EA, et al. Associations of pulmonary microvascular blood volume with per cent emphysema and CT emphysema subtypes in the community: the MESA Lung study. Thorax. 2025 Apr 15;80(5):309–317. doi:10.1136/thorax-2024-222002.

15 Hahn AD, Carey KJ, Barton GP, et al. Hyperpolarized 129Xe MR spectroscopy in the lung shows 1-year reduced function in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Radiology. 2022 Dec;305(3):688–696. doi:10.1148/radiol.211433.

16 Percy JL, McIntosh MJ, Wallat E, et al. Functional imaging of changes in lung function before and after radiation therapy of lung cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2025 Jun 20;10(8):101810. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2025.101810.

17 Sieren JP, Newell JD Jr., Barr RG, et al. SPIROMICS protocol for multicenter quantitative CT to phenotype the lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Oct 1;194(7):794–806. doi:10.1164/rccm.201506-1208PP.

18 Angelini ED, Yang J, Balte PP, et al. Pulmonary emphysema subtypes defined by unsupervised machine learning on CT scans. Thorax. 2023 Nov;78(11):1067–1079. doi:10.1136/thorax-2022-219158.

19 Sieren JC, Schroeder KE, Guo J, et al. Menstrual cycle impacts lung structure measures derived from quantitative computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2022 May;32(5):2883–2890. doi:10.1007/s00330-021-08404-9.

20 Sieren JC, Schroeder KE, Kitzmann J, et al. Ultra-high resolution photon counting detector computed tomography imaging for quantitative lung assessment: an anthropomorphic phantom study. Invest Radiol. 2025 Aug 1. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000001227.

21 AlArab N, McIntosh MJ, Guo J, et al. Comparison of quantitative lung measures in low-dose energy-integrating detector and photon-counting detector chest CT with an anthropomorphic phantom. Biomed Phys Eng Express. 2025 Oct 30;11(6). doi:10.1088/2057-1976/ae0e27.