A Fly Model to Mimic a Rare Chronic Genetic Disease in Patients

Model organisms like Drosophila melanogaster, commonly known as the fruit fly, can help researchers better understand the molecular basis of rare genetic diseases in patients. A single rare disease might affect only a small number of people directly—from a few hundred to several thousand—but rare diseases are collectively common, and their symptoms are often chronic. More than 7,000 rare genetic diseases have been identified, affecting approximately 25 million people in the United States.1 Furthermore, by studying the genetic mutations that cause rare chronic diseases, researchers can identify shared biological pathways and gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying common chronic diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease) and identify new drug targets for developing therapies.

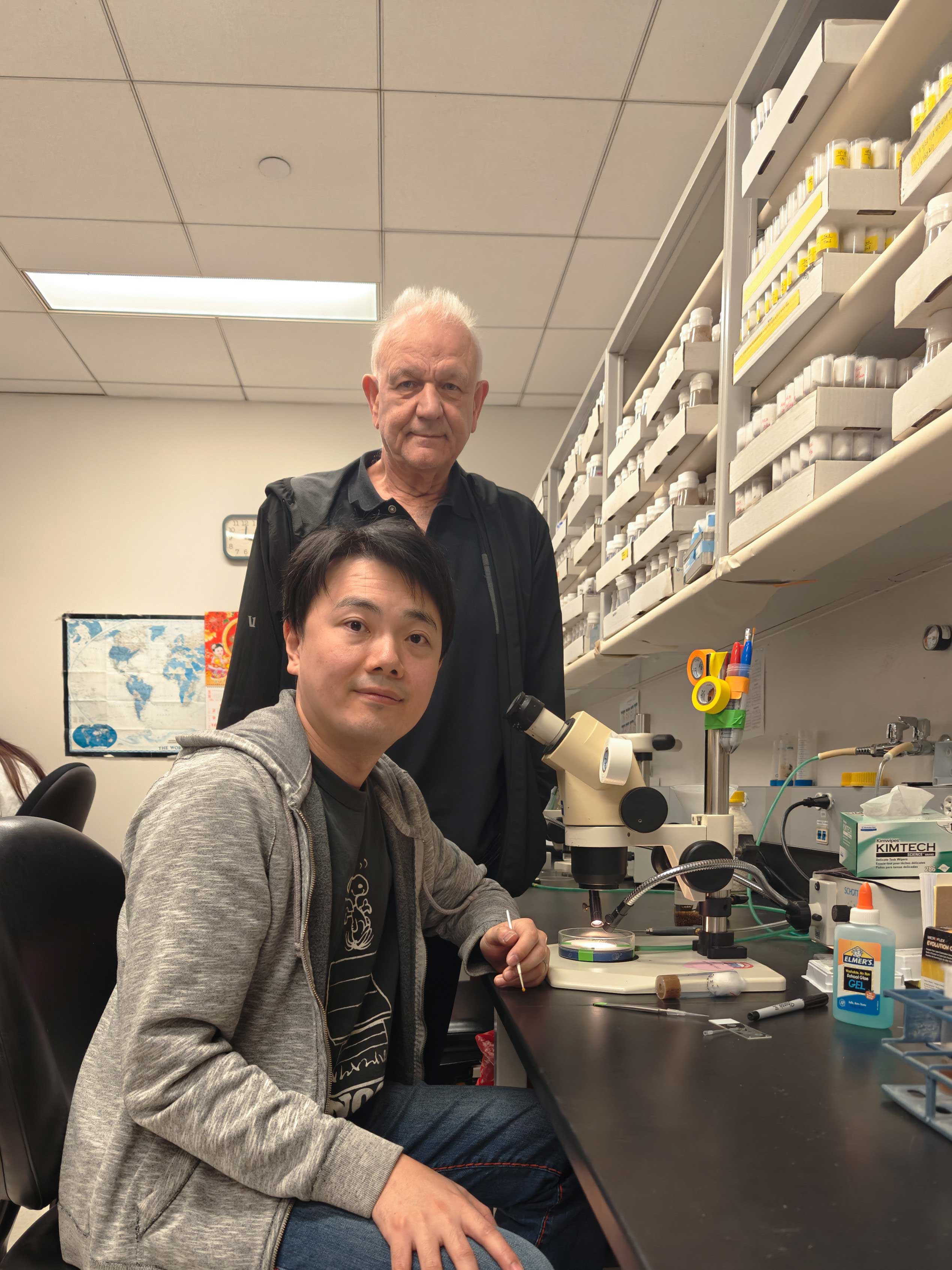

Dr. Xueyang Pan, a former postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Hugo Bellen, Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) (Figure 1), has developed a fruit fly model with Dr. Bellen to help physicians diagnose a disease caused by a mutation in the FRY-like transcription coactivator (FRYL) gene.

FRYL belongs to a highly conserved Furry protein family found in all eukaryotes—from yeast to humans. Humans have two Furry proteins, FRYL and FRY, which originated from one single ancestral gene that duplicated and diverged. These proteins have not been studied in detail, but previous research has shown that they play an important role in a variety of cell functions (e.g., cell shape, cell duplication).

Dr. Wendy K. Chung identified 14 patients in the clinic with genetic mutations in FRYL who have a range of clinical abnormalities. Clinical observations for 13 of these patients demonstrated developmental delays and/or intellectual disabilities (100% of patients), irregular facial structures (79%), cardiovascular defects (50%), autism (42%), seizures (29%), and gastrointestinal complications (21%). The genetic sequencing of 13 of these patients, ranging from 2 years to 20 years of age, showed a FRYL gene mutation that was not inherited from their parents, known as a de novo variant. In addition, Drs. Pan and Bellen found that in flies, a mutation in only one gene copy is necessary for clinical abnormalities to appear.

Dr. Pan remarked, “Before we use animal models, we need to know the conservation of the orthologs—proteins with similar functions—among the species.” The DIOPT (Drosophila RNAi Screening Center Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool) predicted that the fry gene in fruit flies was equivalent to the human Furry genes, FRY and FRYL. This resulting analysis provided the researchers with some confidence that the fruit fly was a possible model for studying the FRYL gene mutations. “We can do a lot of manipulations with flies more easily and quickly than in any other higher eukaryotic model organism,” Dr. Bellen said.

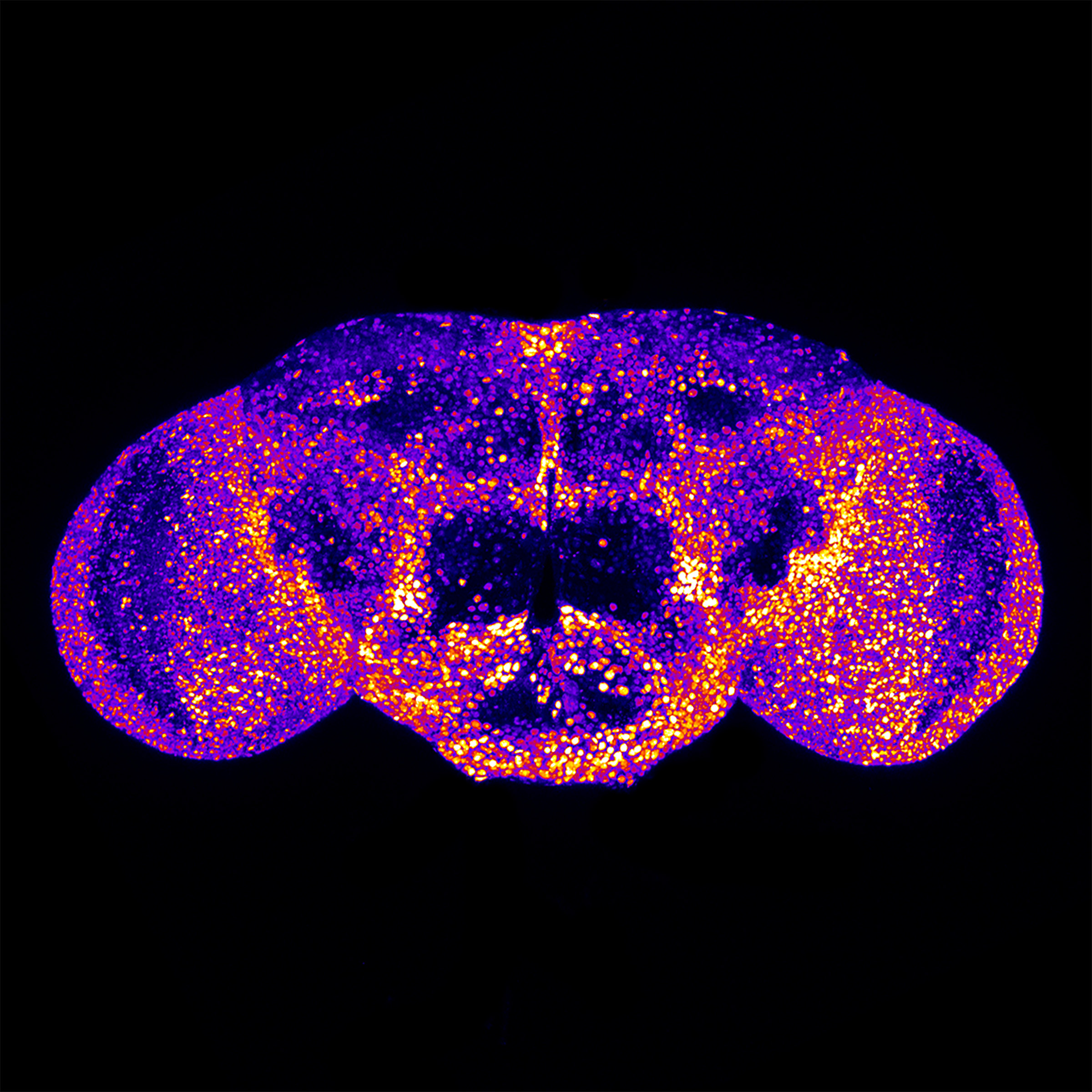

Using gene-editing technology in fruit flies, Drs. Pan and Bellen were able to show that the loss of fry caused death at an early developmental stage. In addition, their research demonstrated that fry expression is cell-type specific. Because most of the human patients had neurological deficits, the researchers focused on the expression pattern of fry in the central nervous system (CNS). In the CNS of D. melanogaster, fry is expressed in neurons—the cells that produce and transmit electrical impulses—but it is not expressed in glia cells, which play a supportive role for neurons (Figure 2).2

The primary aim of this study was to model the genetic variances of FRYL observed in Dr. Chung’s patients to determine whether this gene mutation was the underlying cause of their symptoms. After reviewing the patients’ missense variants (i.e., single nucleotide alterations in the DNA sequence of FRYL), Drs. Pan and Bellen found that four of five of those tested affected the conserved amino acids found in both the human and fly proteins. Using a new gene-editing technique, the researchers mimicked the human FRYL missense variants in the fruit fly. They then identified functional changes originating from the mutations, which included a delay in fruit fly development and vision impairment.2 This finding allowed the researchers to confirm that the FRYL variants in people affect protein function. This genetic disease has recently been named Pan-Chung-Bellen syndrome. “From now on, if physicians sequence a patient’s genome, and they find a variation in the FRYL gene and see the phenotype in the patient as well, they can make a diagnosis,” Dr. Bellen stated.

The Bellen Lab, in collaboration with BCM professors Drs. Shinya Yamamoto, Michael Wangler, and Oguz Kanca, has used the fruit fly model and genetic editing tools to diagnose more than 50 new human chronic genetic diseases, such as Pan-Chung-Bellen.3–6 Drs. Bellen, Kanca, and Yamamoto are the recipients of Resource-Related Research projects (R24OD031447; R24OD022005), which play a pivotal role in developing the genetic toolkit that allows efficient manipulation of fruit flies; their scientific contributions have been reported in a previous ORIP research highlight. Dr. Bellen emphasized the importance of genetic disease research in supporting the collective biomedical community. “By studying the rare disease gene, we can often discover new molecular features of common diseases, which is an important feature of all these studies.” He elaborated that studying the underlying mechanisms of numerous rare disease genes has led to the discovery of key features in well-known neurological diseases—including the role of elevated sphingolipid levels in Parkinson’s disease and lipid droplet formation in Alzheimer’s disease.7–8

The researchers also highlighted how this study is part of a larger effort of the ORIP-funded BCM Center for Precision Medicine Models (CPMM), which is focused on helping clinicians diagnose patients by developing precision animal models for human disease–associated genetic variation. Dr. Chung had submitted a request to the CPMM to model the patient genetic variants of FRYL. After the request was approved, Drs. Pan and Bellen worked closely with her to ensure that the data collected were clinically relevant and provided valuable insights for her patients.

Dr. Lindsay Burrage, Co-Director of the CPMM, stated, “Medical geneticists and physicians are encountering these variants in genes of uncertain significance on genome reports in the clinic every day, and they don’t know how to provide answers to these patients because of the uncertain significance. These patients are then sitting undiagnosed for years in some cases, waiting for an answer.” Dr. Burrage explained that clinicians have limited resources to complete research that would lead to diagnoses for their patients. She emphasized that the CPMM fulfills this knowledge gap and provides the necessary resources to generate preclinical models for these gene variants by working with researchers who have expertise in these areas. The workflow, capabilities, and impact of the BCM CPMM have been reported in an ORIP research highlight. Dr. Bellen included that an additional benefit to developing these animal models is that they serve as a platform for testing drugs to find potential therapies for these patients.

Dr. Bellen underscored the importance of ORIP funding for animal model development and rare chronic genetic disease research. Dr. Burrage added, “As we’re making these models, we are fine tuning and improving our technology, which allows us to have more impact. By making these models more efficiently, we can help more patients faster.” The CPMM is a recipient of an ORIP Pilot Centers for Precision Disease Modeling grant (U54OD030165), which aims to link personalized medicine efforts in patients with advancements in animal genomics and genetic editing technologies to develop precision animal models with enhanced value. The preclinical pipelines developed from this ORIP-funded program will play an integral role in diagnosing, caring for, and treating patients. More information on ORIP-supported research can be found on ORIP’s website.

References

1 Tisdale A, Cutillo C, Nathan R, et al. The IDeaS initiative: pilot study to assess the impact of rare diseases on patients and healthcare systems. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021 Oct 22;16(1):429. doi:10.1186/s13023-021-02061-3.

2 Pan X, Tao AM, Lu S, et al. De novo variants in FRYL are associated with developmental delay, intellectual disability, and dysmorphic features. Am J Hum Genet. 2024 Apr 4;111(4):742–760. doi:101016/j.ajhg.2024.02.007.

3 Moulton MJ, Atala K, Zheng Y, et al. Dominant missense variants in SREBF2 are associated with complex dermatological, neurological, and skeletal abnormalities. Genet Med. 2024 Sep;26(9):101174. doi:10.1016/j.gim.2024.101174.

4 Dutta D, Kanca O, Shridharan RV, et al. Loss of the endoplasmic reticulum protein Tmem208 affects cell polarity, development, and viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2024 Feb 27;121(9):e2322582121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2322582121.

5 Chung H, Mao X, Wang H, et al. De novo variants in CDK19 are associated with a syndrome involving intellectual disability and epileptic encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2020 May 7;106(5):717–725. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.04.001.

6 Guo H, Bettella E, Marcogliese PC, et al. Disruptive mutations in TANC2 define a neurodevelopmental syndrome associated with psychiatric disorders. Nat Commun. 2019 Oct 15;10(1):4679. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12435-8.

7 Goodman LS, Ralhan I, Li X, et al. Tau is required for glial lipid droplet formation and resistance to neuronal oxidative stress. Nat Neurosci. 2024 Oct;27(10):1918–1933. doi:10.1038/s41593-024-01740-1.

8 Lin G, Wang L, Marcogliese PC, et al. Sphingolipids in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Feb;30(2):106–117. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2018.11.003.