S10-Funded Instrument Yields Data for FDA Approval of New Drug for Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older adults and is estimated to affect more than 6 million people in the United States. For decades, the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s disease remained elusive to researchers, and confirmed cases could only be diagnosed by brain biopsy (a procedure that involves removing a small tissue sample from the brain) or autopsy. In the 1990s, this diagnostic challenge inspired Dr. Tammie Benzinger—then a medical student—to harness the power of new imaging technologies to uncover the mysteries of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. “I could see how rapidly our technology was changing,” Dr. Benzinger recounted. “I just had this hope and dream that someday we could actually identify Alzheimer’s disease based on imaging.”

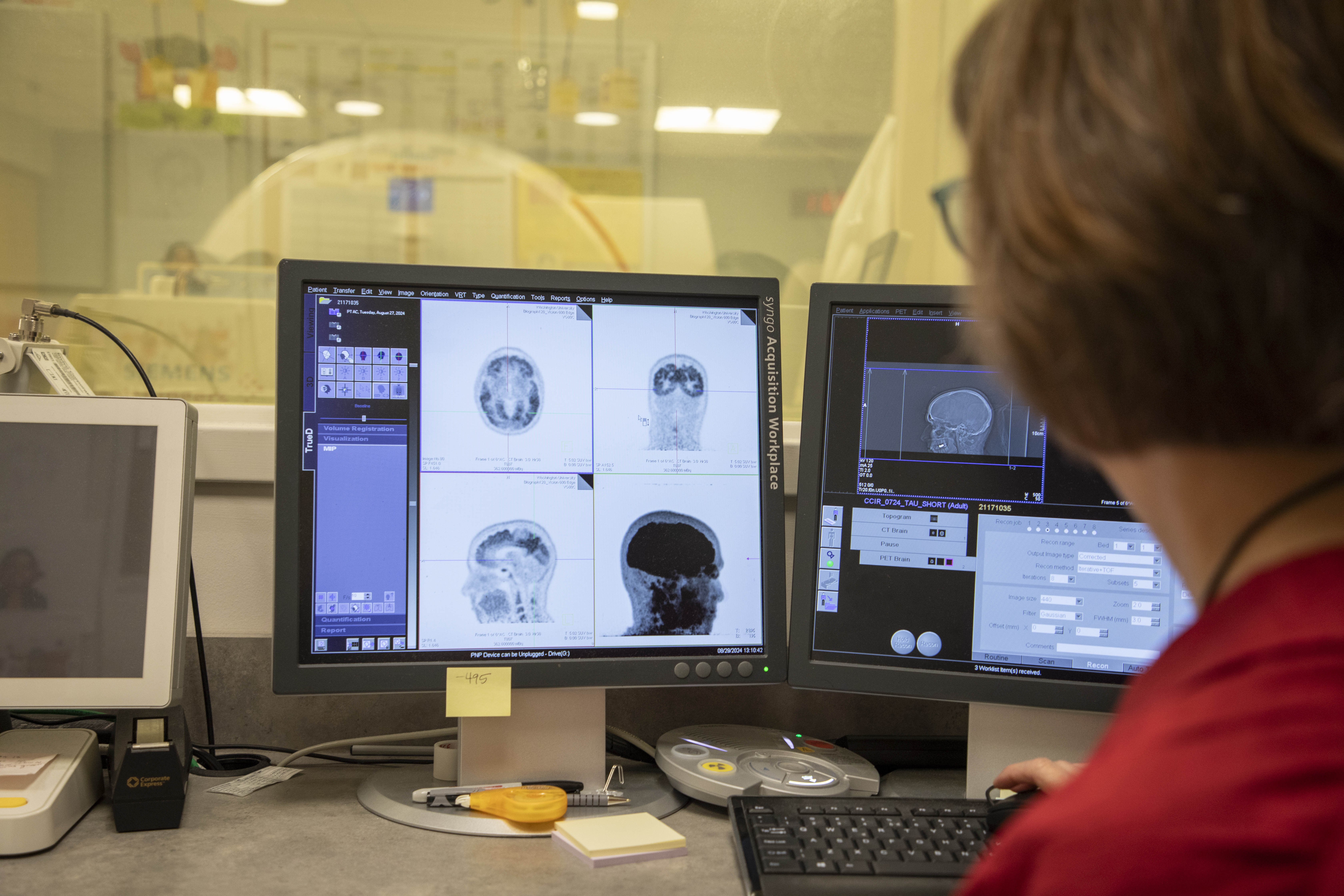

Today, Dr. Benzinger is the Hugh Monroe Wilson Professor of Radiology and Chief of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Service at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University (WashU) School of Medicine in St. Louis. Her research team uses MRI and positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scanning to study biomarkers for detecting and diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, before symptoms arise, just as she originally envisioned (Figure 1).

Dr. Benzinger conducts research at WashU’s Center for Clinical Imaging and Research (CCIR), a centralized, hospital-based research facility that provides access to advanced clinical imaging technologies and resources needed for clinical research studies. Among the CCIR’s advanced imaging systems are two Siemens Biograph Vision 600 PET/CT scanners, one of which was funded (S10OD025214) through ORIP’s S10 Shared Instrumentation Grant Programs in 2018. This funding was critical for investigators at CCIR; despite their recognized importance for biomedical and clinical research, few PET scanners are available or affordable to researchers across the country, as most scanners are reserved for use in oncology patients.

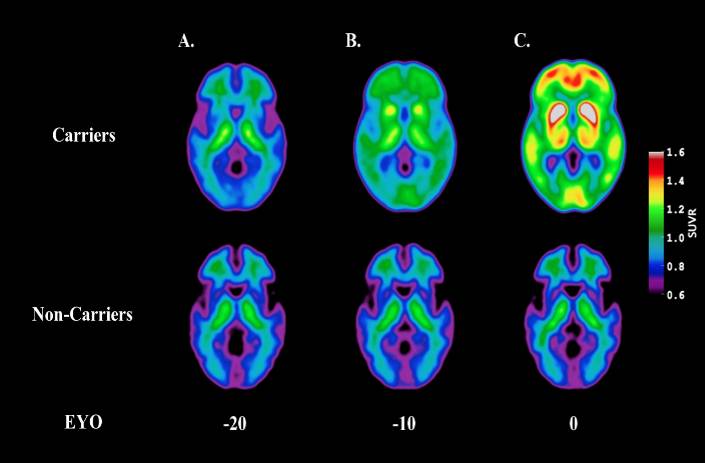

PET scanners are instruments that can generate highly detailed images of a person’s body structures and organs, including the brain. With this noninvasive technology, researchers can view amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles—the two hallmarks of Alzheimer’s—in a patient’s brain. PET imaging allows researchers to track disease progression and visualize the effects of treatments in real time (Figure 2).1–3 “PET imaging has revolutionized the way that we conceptualize this disease,” Dr. Benzinger reflected. “The things that you need for the clinical trials to work take a lot of precision, and the research instruments funded by S10 grants are critical for that.”

The CCIR’s PET scanners were used in a clinical trial that tested the efficacy and adverse events of donanemab4, an antibody designed to clear amyloid plaques in early symptomatic Alzheimer’s that was recently approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in July 2024. Clinically, PET scans view amyloid plaques via a “visual read”; they report the presence of plaques as either positive or negative, without quantification. However, for the donanemab trial, the team needed quantitative metrics to demonstrate, with high precision, the burden of amyloid and tau pathology in the brain before and after treatment with donanemab. In coordination with the other trial centers involved in this study, CCIR used their high-quality scanners with more precise measurements to show that donanemab slowed clinical progression of the disease in early symptomatic patients.

WashU has been a leader in advancing imaging research; some of the world’s first PET scanners were invented and built by hand on campus. In this innovative environment, Dr. Benzinger and her colleagues were among the first researchers to study Alzheimer’s disease using this technology. Over time, the CCIR has continued to acquire equipment to meet growing research needs. Shortly after acquiring the S10-funded instrument, the center raised funds for a second identical scanner, which allowed researchers to obtain data more quickly while maintaining consistency across measurements. More recently, WashU was awarded an additional S10 grant (S10OD034284) to purchase a whole-body human 7-T MRI scanner (MAGNETOM-Terra.X), which was installed in mid-September 2024. WashU is also supported by multiple NIH grants that provide training opportunities for clinician scientists, postdoctoral associates, and Ph.D. and predoctoral students—who are future clinicians and researchers—on the use and operation of imaging instruments.

With these new technologies, the days of relying on brain biopsies to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease are long gone. However, PET scanning still has several drawbacks—such as expense and accessibility—that limit its utility as a diagnostic tool in widespread clinical practice. Dr. Benzinger’s hope is that we will see further validation of blood tests, which would allow clinicians to quickly diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in patients and at low cost. These tests are currently being evaluated against well-established PET scanning methods and protocols—supported by NIH funding (R01AG061900) and performed using the same S10-funded scanner5—showcasing the need for continued support of high-end instruments in critical biomedical research. Dr. Benzinger stated that the S10 programs have been essential for making advanced technologies accessible to biomedical researchers. “Having a scanner that can be used for research is particularly important to us,” she emphasized. “Researchers benefit greatly from NIH-supported facilities and infrastructure.”

ORIP’s S10 programs support purchases of state-of-the-art, commercially available instruments to enhance research of NIH-funded investigators. S10 awards are made to domestic public and private institutions of higher education, as well as nonprofit domestic institutions, such as hospitals, health professional schools, and research organizations. Every instrument awarded by an S10 grant is to be used on a shared basis, which makes the programs cost efficient and beneficial to thousands of investigators in hundreds of institutions nationwide. For more information, please visit ORIP’s S10 Instrumentation Programs webpages.

References

1 McKay NS, Gordon BA, Hornbeck RC, et al. Positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging methods and datasets within the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN). Nat Neurosci. 2023;26:1449–1460. doi:10.1038/s41593-023-01359-8.

2 Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TLS, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1202753.

3 Benzinger TLS, Blazey T, Jack CR, et al. Regional variability of imaging biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(47):E4502-9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317918110.

4 Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512–527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239.

5 Li M, Li Y, Schindler SE, et al. Design and feasibility of an Alzheimer’s disease blood test study in a diverse community-based population. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(12):5387–5398. doi:10.1002/alz.13125.