Profile of a Veterinary Scientist: Rachael Wolters, D.V.M., Ph.D.

Respiratory viruses—including SARS-CoV-2 and influenza—have affected public health significantly in recent years. Dr. Rachael Wolters, a recent graduate of the Ph.D. program at the Vanderbilt Vaccine Center at Vanderbilt University, studies how to use antibodies to protect infants from viral diseases, such as influenza and HIV. Dr. Wolters is the recipient of an ORIP Special Emphasis Research Career Award (SERCA) K01 (K01OD036063), which helped her find her path to an independent faculty position.

While in veterinary school, Dr. Wolters became interested in infectious diseases, and a summer research program introduced her to virology when the Zika virus was prominent in the news. After graduating from The University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine in 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Wolters began her Ph.D. studies in the laboratory of Dr. James Crowe, Director, Vanderbilt Vaccine Center, who has long been interested in the use of monoclonal antibodies as drugs. “The idea that we can dig into the human immune system and identify these potent antiviral molecules and test them as therapeutic candidates was such an exciting idea for me,” Dr. Wolters said. The use of monoclonal antibodies as a treatment for COVID-19 changed the general attitude toward them and their potential applicability. “When I was in veterinary school, monoclonal antibodies were considered a first-world solution,” Dr. Wolters said. “But during the pandemic, it really changed. We can make these more affordable and more accessible in a way that was not previously the case.”

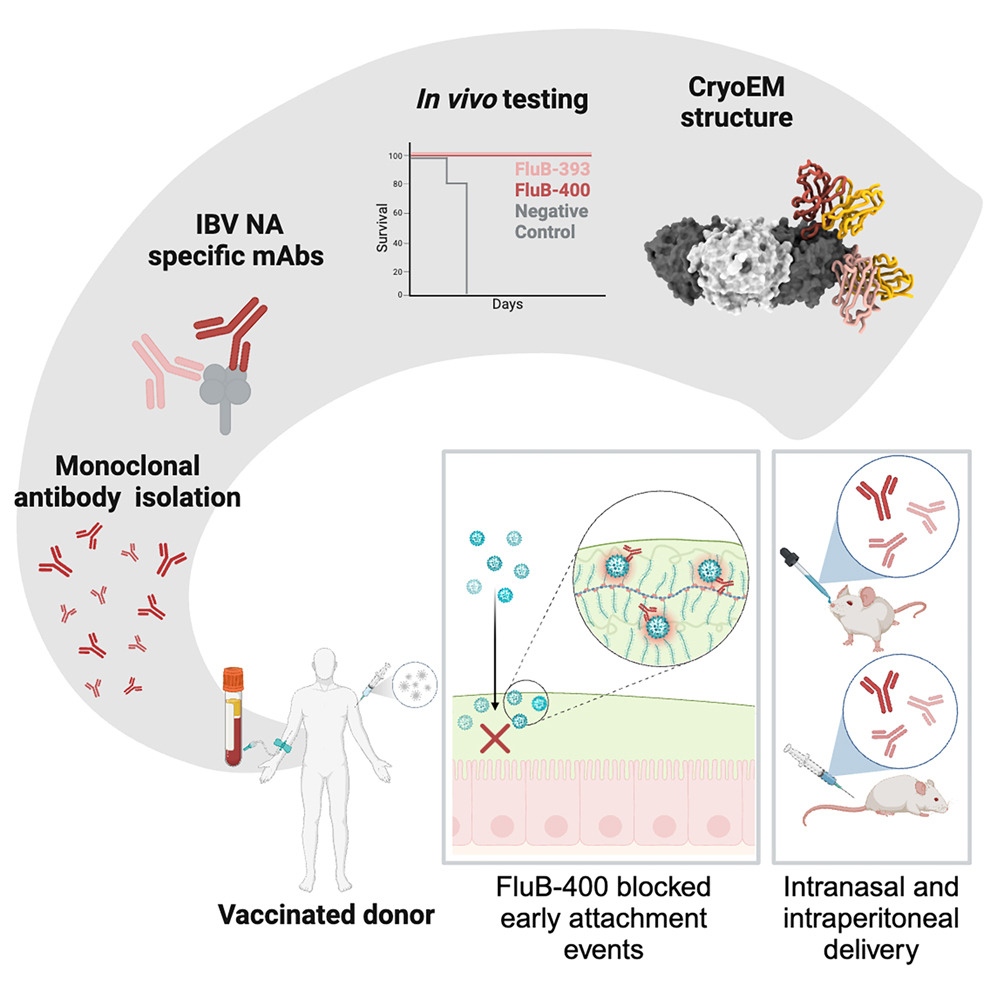

Dr. Wolters focused her Ph.D. research on monoclonal antibodies for influenza (Figure 1); during this time, she applied for the ORIP SERCA K01 award, which helped support and guide her research career. “When I was in veterinary school, I knew that I could be a scientist, but how exactly to go about that was very unclear to me,” Dr. Wolters said. “The K award was really instrumental in helping me understand and financially support that career path, and I was very fortunate to receive that at a really critical moment in my professional development.” The research she conducted while earning her Ph.D. focused on identifying monoclonal antibodies from humans with exposure to influenza type B, one of the types of flu that circulates each year. A publication in Immunity focused on two antibodies: FluB-393 and FluB-400.1 Dr. Wolters’ work showed that both antibodies potently and broadly inhibit influenza type B neuraminidase, a virus protein: FluB-400 by blocking the active site and FluB-393 by inhibiting the enzymatic activity by binding outside of the active site. “Not a whole lot of attention had been drawn to non–active site antibodies,” Dr. Wolters explained, “so this paper describes that both of those epitopes could be protective.” FluB-400 also was able to protect mice from disease when administered intranasally, which supports the future development of nebulization delivery strategies for antibodies (Figure 2). Dr. Wolters is particularly passionate about finding methods to protect infants and other vulnerable groups from viral infections, and intranasal delivery of monoclonal antibodies shows promise in this area.

Dr. Wolters initially was inspired in her career path by the competence and intelligence of the veterinarian who treated her family’s sheep on their farm. However, she was very sick as a child with an undiagnosed immunological illness, and her doctors advised her parents that she should delay college until she was more stable. “Thankfully, I was able to get a diagnosis right before I graduated high school, and that diagnosis came from Vanderbilt,” Dr. Wolters said. “My experience in biomedical research institutions as a kid gave me the impression that people there are really helping.” She carried this impression through her early school years, and her interest in research persisted through veterinary school. “When I defended my Ph.D. this spring at the university that gave me a lifesaving diagnosis as a child, it all felt so full circle,” Dr. Wolters said. “Biomedical research and physician scientists changed my life.”

Dr. Wolters emphasized the importance of the ORIP SERCA K01 award in supporting her ability to pursue an academic research career. “Very few veterinarians have the opportunity to do something like this,” she said. “The K award was able to give me the time and several years of salary support to establish my own research portfolio and figure out what I want to do as a scientist. Being an early-career investigator is pretty intimidating, and being a scientist in infectious disease, it’s harder than ever to find funding to support your science.” She also noted the guidance and support provided by ORIP throughout the process. “The people at ORIP have always seen me as someone that they are trying to support rather than one of the many fighting for federal dollars. I know that even though it is an uphill battle, there are people trying to teach folks like me how to navigate it.”

“Being a veterinarian brings both a lot of insight into animal models and a lot of responsibility,” Dr. Wolters said. “I took an oath to do no harm, and I also took an oath to public health as a veterinarian. And so, I’m often carrying both of those burdens when I think about the use of animal models in biomedical research. I think it’s very important to include veterinarians in biomedical research because we’re able to hold those priorities.” She noted that the training veterinary scientists undergo emphasizes the importance of upholding both those values.

Dr. Wolters recently joined the faculty of the Oregon Health & Sciences University Division of Pathobiology and Immunology at the Oregon National Primate Research Center, where she studies the protective role of broadly neutralizing antibodies in the context of mother to child transmission of HIV. “During my time at Vanderbilt, I established several mouse models, which are such a powerful tool for incredibly rigorous and meaningful science,” Dr. Wolters said. “And now I’m transitioning to nonhuman primates—again, a super-powerful model, but one that is very different.” Dr. Wolters emphasized that her training as a veterinarian has made her more confident in making decisions about such a complex animal model. “In working with infant nonhuman primates, we have to balance the science with this vulnerable animal model that, much like human babies, will catch a cold,” Dr. Wolters explained. “That is where being a veterinarian is super helpful, because although I’m wearing a researcher hat, I’m working hand in hand with our clinical veterinarians, and we’re able to make decisions about these animals and how to move the studies forward.”

“I am really thankful for ORIP’s commitment to veterinary scientists, and I very much credit them for creating one of the few very clear pathways for us to be a part of the academic biomedical profession,” Dr. Wolters said. “I hope that NIH and funding agencies continue to make that a priority.”

ORIP supports training and career development programs specifically for veterinarians seeking to enter the field of biomedical research. Scientists with veterinary medical expertise contribute to animal, molecular, and genomic studies and translational research that benefits human health. More information on ORIP’s training programs can be found through ORIP’s Training and Career Development Resources fact sheet.

Reference

1 Wolters RM, Ferguson JA, Nuñez IA, et al. Isolation of human antibodies against influenza B neuraminidase and mechanisms of protection at the airway interface. Immunity. 2024;57(6):1413–1427.e9. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2024.05.002.