Profile of a Promising Environmental Health Scholar: Tracie Baker, D.V.M., Ph.D.

An environmental toxicologist, principal investigator, and director of the Warrior Aquatic, Translational, and Environmental Research (WATER) Laboratory, Dr. Tracie Baker (Figure 1) has long had an interest in studying aquatic animals, an interest that eventually led to toxicology research and the opportunity to lead a Florida Everglades research expedition.

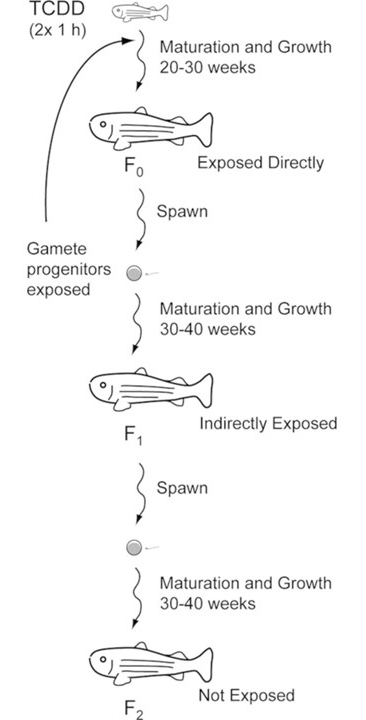

Dr. Baker received a dual bachelor’s in biology and chemistry from Cleveland State University. She earned her master’s in marine biology from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, where her research focused on the toxins produced from harmful algal blooms and human effects. She then attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison for her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree, focusing on fish and aquatic animals. Dr. Baker continued her studies at the University of Wisconsin to earn a Ph.D. in molecular and environmental toxicology. There, she was introduced to the zebrafish model by her thesis advisor and mentor, Dr. Richard Peterson. The zebrafish is an excellent model to study human health and disease, and she was the first to use this animal model to investigate transgenerational toxicity (Figure 2)—specifically, the environmental contaminant 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin).

While she was conducting research in Dr. Peterson’s laboratory, Dr. Baker was awarded an NIH Special Emphasis Research Career Award (SERCA) K01. The ORIP Division of Comparative Medicine funds SERCAs in pathology and comparative medicine to assist graduate veterinarians who have experience in animal and comparative research to become independent investigators in areas related to biomedical science. A SERCA K01 emphasizes an in-depth mentored research experience in basic or clinical scientific disciplines and provides up to 5 years of support for individual grantees.

In her proposal, Dr. Baker highlighted that one important step toward improving human health is understanding how exposure to environmental toxicants during gestation and childhood leads to disease later in adulthood. She expanded her research to use the zebrafish model to understand toxic responses seen in adult fish exposed to TCDD at low levels during development. Dr. Baker discovered that low-level, dioxin-induced decreased fertility, which is evident across multiple generations following early developmental exposure, is mediated through the male germline.1,2 She presented these findings at several national and international conferences, including at NIH-hosted workshops.

The K01 enabled Dr. Baker to publish several articles from 2013 to 2016, when she transitioned to her first faculty position and started her own research laboratory at Wayne State University. Dr. Baker’s laboratory—the WATER Laboratory—is focused on multidisciplinary translational research that seeks to bridge and improve human, animal, and environmental health. She received R01 funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to investigate epigenetic mechanisms of how endocrine disruptors are causing transgenerational changes, focusing on male infertility. Her research also has branched into looking at other endocrine-disrupting compounds in this context—specifically emerging contaminants, such as microplastics, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and personal care products. In 2021, Dr. Baker accepted a tenured associate professor position at the University of Florida and continued her research.

Dr. Baker remarked, “The K01 was really important to me personally, because it changed the dynamic of my research in the laboratory, moving me from being in someone else’s laboratory to having my own independent funding. It was a launching point for my independent career.” She also noted that the K01 was a great stepping stone to apply for faculty positions, because already having received her own funding and being able to bring funding to a university put her in a favorable position. She credits the K01 with her success in securing subsequent grants and awards. “I feel like I learned a lot from the K01 about grantsmanship, career development, and how to be a successful investigator,” she said.

Another aspect of her work, which began at Wayne State, is conducting scientific field expeditions (Figure 3) that involve travel to different urban and rural areas to determine where many of the emerging contaminants are present in the environment.

She recently completed the 2022 Willoughby Expedition through the Florida Everglades (Figure 4) as lead scientist representing the University of Florida in this collaborative effort. This expedition retraced an 1897 canoe journey that was first completed by explorer and scientist Hugh De Laussat Willoughby and collected water samples from the Gulf Coast, along 130 miles through the Everglades, to the Atlantic coast. These samples will be analyzed for chemistry changes and emerging pollutants. With this expedition, Dr. Baker became the first non-Indigenous woman to make this canoe trek across the Everglades.

Dr. Baker shared key messages for the next generation of environmental researchers. Funding in academia remains essential for being able to do research that scientists are passionate about. “You have to persevere, keep trying, and not let one bad grant review make you decide that you’re not going to keep at it,” she said. Another challenge is maintaining a work–life balance and prioritizing what’s important. She credits her mentor, Dr. Peterson, for encouraging her to pursue a Ph.D.; he was very supportive and taught her what being a good mentor entails. She thinks of this encouragement and his other teachings when she mentors students in her own laboratory. Additionally, she noted that the most important aspect of a career in research is to find one’s passion and then find a comfortable, inclusive space to work and not settle for less. Last, she urged future scientists to pursue their passion and trust the process even when the task at hand seems difficult.

For additional information on the SERCA K01 Scholars Program, visit the ORIP SERCA Guidelines page.

References

1 Baker TR, Peterson RE, Heideman W. Early dioxin exposure causes toxic effects in adult zebrafish. Toxicol Sci. 2013;135(1):241-250. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kft144

2 Baker TR, Peterson RE, Heideman W. Using zebrafish as a model system for studying the transgenerational effects of dioxin. Toxicol Sci. 2014;138(2):403-411. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfu006