Pervasive Effects of COVID-19 on the Brain of Nonhuman Primates

In an article published today in Nature Communications,1 a team of scientists from the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC) reported the first comprehensive assessment of neuropathology associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primate (NHP) models. The work was a product of the Pilot Research Program, a key component of the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) base grant (P51OD011104) that supports all aspects of the Center’s operations. The institution also provided funds to support the completion of the work.

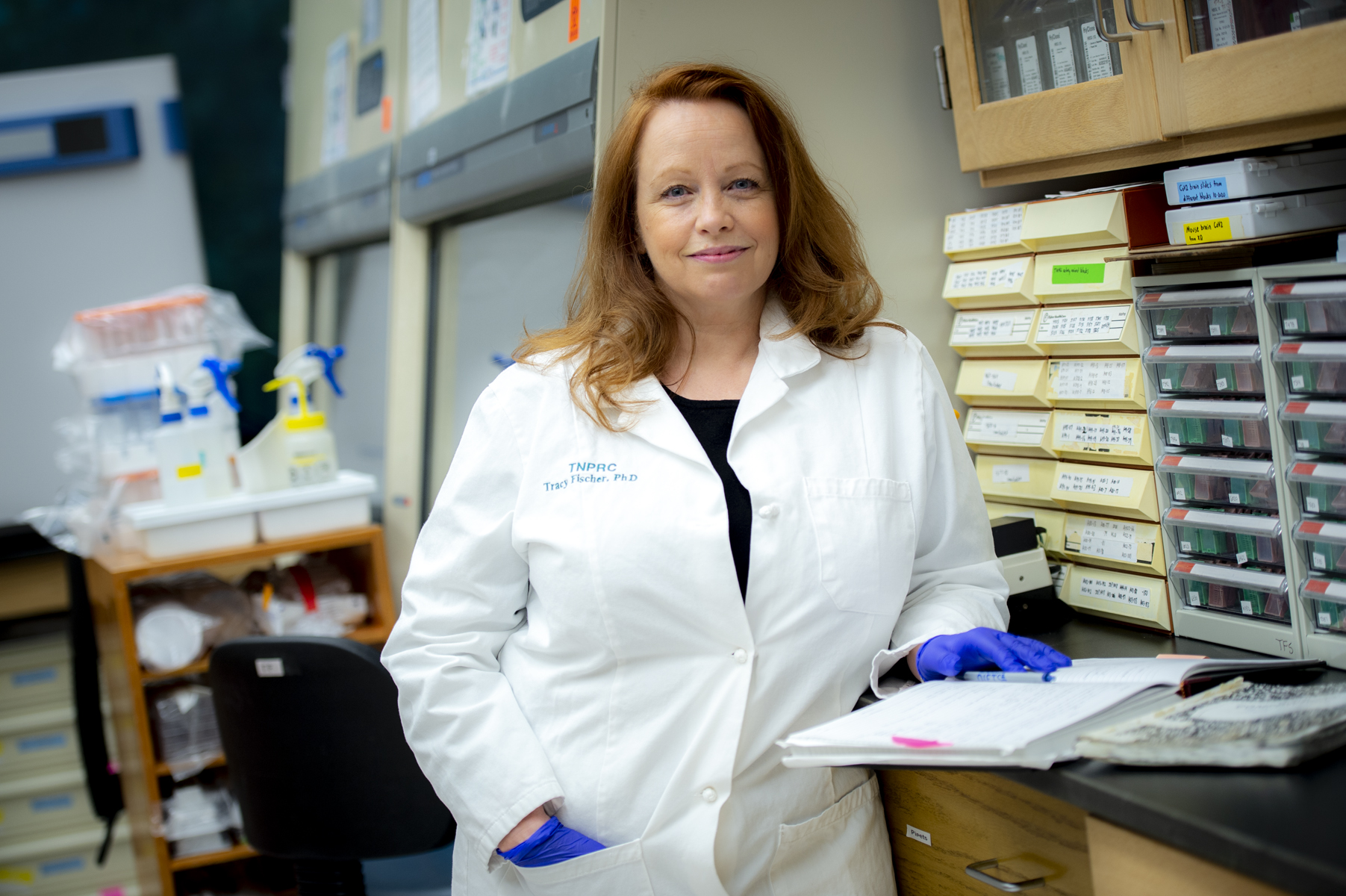

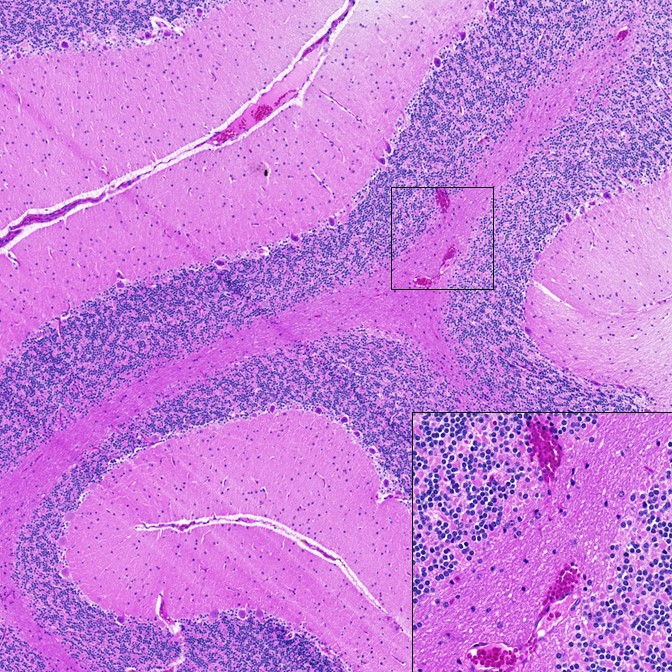

Dr. Tracy Fischer, Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Tulane University School of Medicine (Figure 1), collected data from brains of two NHP species—the rhesus macaque and the African green monkey—that had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dr. Fischer recounted that the team’s initial findings were striking: the brain tissues from infected monkeys showed signs of inflammation, as well as indicators of neuron death and the presence of unique microhemorrhages—tiny lesions that indicate internal bleeding (Figure 2).

“You see the pathology, and it’s so distinct and so profound,” Dr. Fischer stated. “I’ve been looking at the central nervous system for decades, so long that you know when something doesn’t appear normal and appears to be in line with the infection.”

These findings could provide researchers with insight into the potential impact of COVID-19 on the human brain, given the physiological and structural similarities in primate species. Dr. Fischer explained that these pathological effects could impair brain function and may help explain several symptoms of COVID-19 observed in humans, such as persistent headaches and impaired consciousness.

A large body of scientific research regarding COVID-19 is focused on pathology in the lung, the primary site of infection. The researchers at the TNPRC, however, are using NHP models to study COVID-19 from an interdisciplinary perspective. The team is studying the effects of COVID 19 across multiple organs, with a goal of understanding how SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the interplay of physiological systems. The Nature Communications article is the most recent publication from a series of COVID-19 studies by TNPRC investigators that were made possible with support from the Pilot Research Program.

Dr. Jay Rappaport, TNPRC Director and Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Tulane University School of Medicine, explained that the TNPRC investigators pivoted at the beginning of the pandemic to develop NHP models for COVID-19. Because these efforts were carried out at such an early stage of the pandemic, some of the group’s findings, such as the brain microhemorrhages, were observed in the animals even before they had been detected in human patients. Drs. Rappaport and Fischer noted that some of their academic peers initially were skeptical of these early findings, but the team’s well-documented report ultimately demonstrated the validity of their findings.

“I think that takes courage, to go out on a limb. I remember looking at the images, and I could see the red blood cells on the wrong side of the lumen. But at first, a lot of people were not so eager to accept our results.” Dr. Rappaport reflected. “Yet Tracy had the courage, conviction of the findings, and tenacity to do all of those studies—and to use the proper controls—to verify that the original findings are real.”

Dr. Rappaport explained that the TNPRC, which the NIH has supported for 60 years, was well equipped to enable these early, crucial studies on the pathology of COVID-19. The Center maintains a High-Containment Research Performance Core, which provides capabilities for biosafety level 3 and select agent studies. Additionally, the TNPRC is the only National Primate Research Center with an onsite Regional Biocontainment Laboratory. Dr. Rappaport underscored the value of ORIP investments for COVID-19 research at the Center.

“The pilots were highly successful, and the support from ORIP was very important in overcoming the initial financial challenge for this work,” Dr. Rappaport emphasized. “The initial investments have paid off enormously in terms of the number of papers, all that we’ve gained on the models, and all the subsequent studies—therapeutics, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines—that we’ve been able to test based on those models.”

Drs. Rappaport and Fischer conveyed that as the TNPRC continues to foster research related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, its leadership remains mindful of strategies to respond quickly to future pandemics. A central component of this effort is training the next generation of scientists, which is included in the educational component of the Center’s funding. As the Center continues to grow and adapt to the dynamic landscape of biomedical research, the support it receives from ORIP remains crucial for fulfilling its national mission to improve human and animal health through basic and applied biomedical research.

Reference

1 Rutkai I, Mayer M, Hellmers L, et al. Neuropathology and virus in brain of SARS-CoV-2 infected non-human primates. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1745). doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29440-z.