NIH-Funded Gnotobiotic Facility Advances Microbiome Research in Chronic Liver Diseases and Obese Conditions at the University of California, San Diego

Many areas of biological research—including immunology, metabolic disorders, neurology, infectious disease, cancer, and translational microbiome research—require a well-controlled environment to study the role of the microbiome and host–microbe interactions. NIH supports the construction of gnotobiotic facilities that provide such specialized research environments designed to raise and maintain animals—primarily mice—in completely germ-free or precisely defined microbial conditions. Dr. Bernd Schnabl, Director of the San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center (SDDRC) at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), is leading cutting-edge research into the gut–liver axis, a bidirectional communication network between both organ systems that is pivotal in human health and disease. His research focuses on how disruptions in the gut microbiome—the collection of microorganisms (i.e., bacteria, viruses, and fungi) that live in the intestine—contribute to liver disease. Dr. Schnabl’s work has been made possible by an ORIP grant (C06RR017309) awarded to investigators at UCSD that helped establish a gnotobiotic facility.

Dr. Schnabl’s team is studying how disruptions in the intestinal barrier are caused by an altered gut microbiome, a condition known as “leaky gut,” in which the intestinal lining becomes more permeable, allowing undigested food particles, toxins, and bacteria to enter the bloodstream. In a leaky gut, an altered gut microbiome may contribute to liver disease progression in patients with such chronic conditions as alcohol-associated hepatitis and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). “If you eliminate the bad gut microbiome, you eliminate disruptions in barrier function and have dramatically less liver disease,” Dr. Schnabl explained. To study this interaction with precision, his team uses mice raised in germ-free (i.e., free of contamination from bacteria, viruses, fungi, or other microbes) environments.

The C06 grant provided initial funding for Dr. Schnabl to develop the gnotobiotic housing he needed for the animals at UCSD. That facility ultimately grew and became part of the broader SDDRC, now funded through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, P30DK120515). The gnotobiotic facility comprises different types of cages, such as germ-free breeding cages (Figure 1), that provide a gnotobiotic environment. The SDDRC maintains germ-free and gnotobiotic conditions through strict controls to prevent contamination, promote specialized training, and enforce rigorous workflows. “This is a delicate field of work,” Dr. Schnabl explained. “We’ve created a system that ensures consistency and minimizes contamination risks, especially important when testing live bacteriophages or studying bacterial strains.”

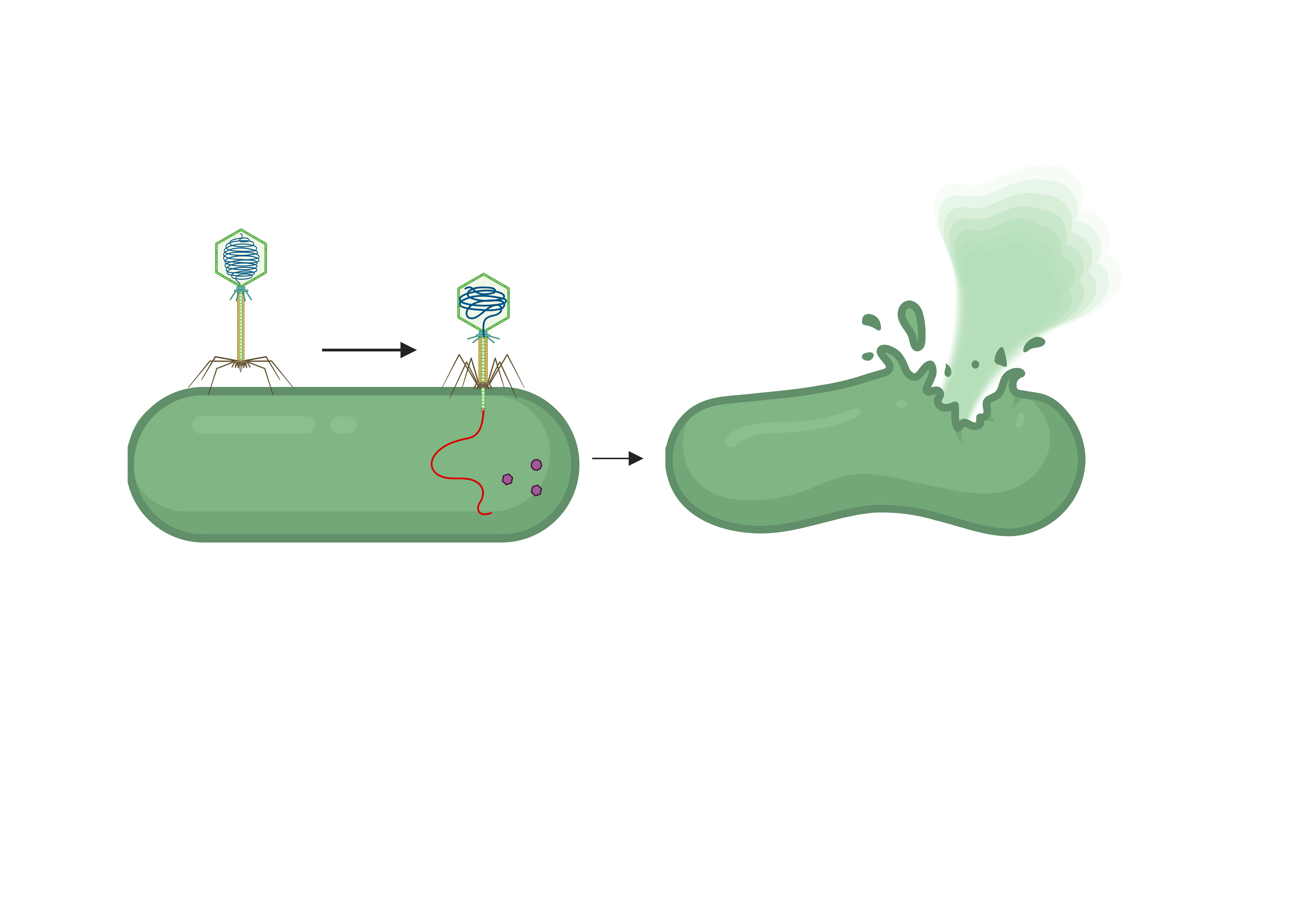

The facility has enabled several high-impact discoveries, such as the identification of a toxin-producing gut bacterium, Enterococcus faecalis, that worsens alcohol-associated hepatitis. This breakthrough enabled Dr. Schnabl’s team to develop and test a novel therapy using bacteriophages, small viruses that can target and kill bacteria associated with specific diseases (Figure 2).1 His team used screening technologies to identify the most effective bacteriophage combinations in mice to treat alcohol-associated hepatitis. These results led to Dr. Schnabl’s founding of Nterica Bio, a biotechnology company that has received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to conduct Phase 1 clinical trials to bring bacteriophage therapy to patients. The gnotobiotic mouse facility also has supported studies on MASLD. In a recent project, Dr. Schnabl’s team transferred stool samples from obese patients into germ-free mice to observe the resulting liver damage, providing insights into how gut fungi contribute to liver disease.2

The SDDRC also has fostered cross-disciplinary research collaboration and mentoring. The SDDRC provides the research community with the much-sought-after germ-free animal models by colonizing defined microbes, administering various experimental agents, and converting mice to a germ-free state through collaboration with the UCSD Animal Care Program. Dr. Schnabl emphasized the wide impact of this facility: “These resources have allowed us to establish not only local but also national and international collaborations; 20% of our publications from the SDDRC have come from national collaborations, and 29% from international collaborations.” Through NIH-funded Pilot/Feasibility and Enrichment programs, early-career investigators receive mentorship, funding, and guidance on grant applications that help them transition into independent research careers. The SDDRC launched a Career Development Club, which offers an opportunity for early-stage faculty to present and discuss projects that are at various stages of grant preparation. Other aspects of career development, such as academic career planning or submission of research papers, are also within the scope of the club. The center supports collaborations across neuroscience, cancer biology, microbiology, and metabolic disease. Additionally, a biobank of human biospecimens is available for researchers to use in translational studies.

Dr. Schnabl underscored the critical role of NIH and ORIP funding: “Without this infrastructure, many of our microbiome studies, and the therapeutic opportunities they’ve created, simply wouldn’t exist. The buildings, maintenance, staffing, and resources make it all possible.” Looking ahead, Dr. Schnabl aims to expand the facility’s capabilities to enable deeper investigations into how host genetics shape microbiome interactions, reiterating that these future directions will not be possible without continued federal funding.

The gnotobiotic mouse facility and broader SDDRC were made possible through ORIP’s Research Facilities Construction Grant (C06RR017309). ORIP’s Division of Construction and Instruments (DCI) funds programs that support the construction, renovation, and modernization of research space by issuing notices of funding opportunities (NOFOs) when congressional appropriations are available. These programs aim to provide modernized physical infrastructure that meets the evolving engineering needs required to conduct cutting-edge NIH-funded biomedical research. These investments benefit nearly all NIH institutes and centers, advancing research across the full spectrum of biomedical sciences, from fundamental biology to clinical translational research.

References

1 Duan Y, Llorente C, Lang S, et al. Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease. Nature. 2019;575(7783):505–511. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1742-x.

2 Demir M, Lang S, Hartmann P, et al. The fecal mycobiome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2022;76(4):788–799. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.029.