Fruit Fly Fourth Chromosome Resource Project Creates New Resources for Biomedical Research

Drosophila melanogaster, commonly known as the fruit fly, is a model organism utilized in biomedical research to understand the conserved molecular mechanisms underlying health and disease. D. melanogaster offers many advantages in the laboratory, including short generation time and the ability to conduct sophisticated genetic experiments inexpensively. “Changing gene expression experimentally at the level of single cells or individual tissues is straightforward for fly geneticists, and the stocks don’t cost much once they’re developed. Similar experiments in vertebrates are mostly out of reach because the resources do not exist or the experiments would be too expensive,” stated Dr. Kevin Cook, Senior Scientist in the Department of Biology, Indiana University Bloomington.

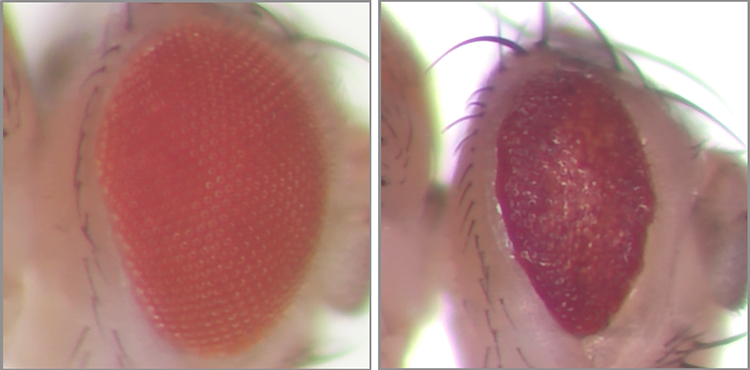

D. melanogaster has been used in research extensively, and analysis of the species has led to numerous findings in physiology and medicine. Since 1933, six Nobel Prize laureates have exploited fruit flies in their groundbreaking discoveries on trait inheritance, the production of mutations by X-ray irradiation, conserved genes in development, embryonic organ growth, innate immune system activation, and circadian rhythm control. Nonetheless, in the Drosophila community, the lack of research resources for the fourth chromosome, also known as the dot chromosome, has long been a concern (Figure 1). Many standard genetic approaches are impractical for studying fourth chromosome mutations due to the chromosome’s small size, extensive runs of repetitive sequence, and lack of DNA recombination. These technical barriers have led scientists to overlook the fourth chromosome. Nevertheless, the fourth chromosome remains of vital interest to researchers because it contains many essential and conserved genes.

To overcome the challenges that have historically limited studies on the fourth chromosome, Dr. Stuart Newfeld, Professor in the School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, proposed a collaborative project with Dr. Michael O’Connor, Professor and Department Chairperson for the Department of Genetics, Cell Biology, and Development, University of Minnesota, to create stocks that mark cells that have lost the activity of a fourth chromosome gene with green fluorescent protein (GFP).1,2 Using these stocks, gene activity can be eliminated in specific cells or tissues according to the experimental needs of researchers, and affected cells can be easily identified with GFP. This method is particularly valuable when an inherited loss-of-function mutation in a gene would cause the fly embryo to die. This method facilitates studying later developmental stages and understanding the gene’s role in adults.3

The goal of the Fourth Chromosome Resource Project (FCRP) is to overcome the technical barriers to examining genes on the fourth chromosome and to make this chromosome as easy to analyze genetically as other chromosomes. FCRP investigators have achieved this goal by creating five classes of D. melanogaster stocks, each of which contains a distinct genetic modification.

The first class allows investigators to express fourth chromosome genes in selected cells or tissues using the GAL4–UAS gene expression system, in which the GAL4 transcriptional activator expressed from one transgene drives expression of a gene under the control of UAS regulatory sequences in another transgene. The proteins expressed by the UAS transgenes in these stocks are tagged with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope—a protein marker that can be recognized by antibodies—for easy detection and visualization (Figure 2). The second class expresses the GAL4 transcriptional activator in place of a fourth chromosome gene to explore natural gene expression patterns and drive the expression of UAS transgenes in those patterns. The third class of stocks allows substitution of the comparable human gene matching a fly fourth chromosome gene to study differences in protein activities between the two species (Figure 3). The fourth class of stocks allows the study of cellular and subcellular protein localization by tagging the proteins expressed by fourth chromosome genes with GFP. The fifth class is an expanded repertoire of stocks, built on the technology created in the original collaborative project, with mutations that eliminate gene activity in specific cells or tissues. Each class of stocks has a unique utility for genetic analysis.

Before the FCRP, 58% of the protein-coding genes on the fourth chromosome did not have even a single genetic tool available and were largely unstudied. As of March 2025, the FCRP has significantly expanded the ability of researchers to study Drosophila, with 750 publicly available stocks covering all the classes noted above. The FCRP team also generated the first set of phenotypic data on the unstudied genes and significantly increased the fraction of protein-coding genes with mutations.4 “With the creation of these stocks, the sky is the limit. The investigators’ creativity is the only limitation in terms of understanding diseases, and areas of public health can be advanced based on our tools,” Dr. Newfeld stated. Dr. O’Connor elaborated, “If you get a clear phenotype in the fly from a mutation that has an equivalent human disease mutation, you can utilize the genetics of the fly to identify what will suppress the phenotype. That might identify a pathway that you could manipulate by designing a drug to help alleviate symptoms of the disease.” To date, FCRP researchers induced mutations in 62 protein-coding genes and characterized novel phenotypes for 35 of them.4

D. melanogaster stocks created through the FCRP are sent to the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) at Indiana University Bloomington, with more than 800 samples shipped to investigators in the fly research community. Investigators have been implementing the resources generated by the FCRP to elucidate mechanisms underlying a broad range of health and disease topics. For example, FCRP stocks have been used to examine the intricacies of gene expression in insulin-producing cells and circadian pacemaker cells.2

The BDSC—which is co-funded by ORIP, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke—provides care for more than 90,000 fruit fly stocks, including those developed by the FCRP, that are available for investigators to purchase and integrate into their research efforts. The center is the only repository and distribution facility for genetically characterized strains of D. melanogaster in the United States.

The BDSC has more than 7,800 registered investigators who collectively place many thousands of Drosophila orders annually. In 2024, the BDSC shipped 156,466 D. melanogaster stock samples to more than 2,400 scientists. A recent survey showed that BDSC stocks support at least 837 NIH extramural grants and several NIH intramural research programs, as well as hundreds of laboratories that receive other sources of funding.

Dr. Kumar emphasized how vital ORIP-funded programs and resources are to advancing scientific understanding of human health and disease. He explained, “These resource projects help lots of laboratories across the world, not only those that study Drosophila. Researchers who study conserved genes in other model organisms can refer to data that we generate in D. melanogaster as a foundation. Principal investigators studying zebrafish, mice, and primates can take advantage of FCRP data as a launchpad for their own studies.”

References

1 Goldsmith SL, Shimell MJ, Tauscher P, et al. New resources for the Drosophila 4th chromosome: FRT101F enabled mitotic clones and Bloom syndrome helicase enabled meiotic recombination. G3 (Bethesda). 2022;12(4):jkac019. doi:10.1093/g3journal/jkac019.

2 Goldsmith SL, Newfeld SJ. dSmad2 differentially regulates dILP2 and dILP5 in insulin producing and circadian pacemaker cells in unmated adult females. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280529. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280529.

3 Stinchfield MJ, Weasner BP, Weasner BM, et al. Fourth Chromosome Resource Project: a comprehensive resource for genetic analysis in Drosophila that includes humanized stocks. 2024;226(2):iyad201. doi:10.1093/genetics/iyad201.

4 Weasner BM, Weasner BP, Cook KR, et al. A new Drosophila melanogaster research resource: CRISPR-induced mutations for clonal analysis of fourth chromosome genes. G3 (Bethesda). 2025;15(3):jkaf006. doi:10.1093/g3journal/jkaf006.